The Indian-American volunteer unfurling layers of migration, identity and privilege

Hello, my name is Mahima Shah Verma. I am 21 year-old individual from a suburban city called Irvine in the state of California in the country of the United States of America.

I am a first generation Indian American, according to my passport, born and raised in a city built in 1971 on top of hundreds of acres of Valencia Orange groves. Three weeks ago, I moved to Berlin in search of self after graduating from college.

To document the work of GSBTB Open Art Shelter on social media these upcoming five months while I am a student at Freie Universität, I will share my biases and experiences concerning the situation of resettled individuals and families in Berlin to my fellow team members in respect of the privileges I have been given to document their incredible compassion and strength.

I do not intend to remind individuals of their traumas in my disclosure of my personal experiences that have shaped my values and the skills and passion I can bring to this team. I welcome all viewpoints without expectations of your reciprocity and apologize sincerely to those who I have not addressed respectfully in this endeavor.

I write in the sole hope that piece will start our conversations about togetherness, learning, and self compassion as we work together each week with young children growing up in families inheriting constantly redefined, dehumanized statuses under long-term conditions of exclusion.

During the year following the summer I had volunteered in transit camps for displaced families and individuals from Afghanistan, Syria, Pakistan, and Cuba in Hungary and Serbia (July-Aug. 2016), I confronted my personal trauma and lifelong motivations of humanitarian assistance.

I grew up learning about India and its culture from my grandmother, who would visit every year for six months and read us stories of gods reincarnated as princes at bedtime. I learned about my parent’s culture through the Hindustani classical and Bollywood dance classes and the warm lentils and vegetables my mother cooked on the stove in the evening. I learned about poverty witnessing children starving on the streets from the window of the cars I took to my dad’s offices or construction sites in India each winter or summer school holiday.

I did not know whether to call my consciousness:

immigrant or minority?

my appearance:

Indian or American or both?

I looked like one and acted like another, at least this is what college recruiters expected of me.

Growing up in a predominantly Asian American community overworking their children under impossible standards of success, I quickly learned that an “A-” is not an “A,” in simple terms you cannot afford inferiority as a child of sacrifices made oceans away.

I grew up isolated linguistically and culturally from the few Indian Americans I went to school with, growing up in a neighborhood where brownness of skin meant one was Hispanic or Latin American. Hindi and Spanish became my second languages as I was taken care of by various women from Latin America and Mexico living in poverty and restricted visas when my parents worked abroad. At least, us Indian Americans, parents conveyed at dinner parties, weren’t supposed to be friends if we both wanted to get into the same college.

When I returned from Hungary and Serbia last summer to my university in Los Angeles in August 2016, I experienced an indescribable pain. The surface of discrimination that pushed me towards hidden roots of self-destruction:

Grief that I could leave inhuman conditions of camps because of the soil I was born on, but these children could not.

Anger at the violent words and actions of volunteers who told the people they were helping to “go back to your country.” The local Serbian police who told the homeless people arriving from the Bulgarian and Croatian border they were protecting “you are terrorists.”

Shame serving meals to hundreds of displaced men left homeless at the Belgrade bus station, hearing their whistles and sexual remarks of my bare arms in Hindi and Urdu and calling me a “didi” (sister) responsible for their wellbeing. And then hearing these men’s respectful, English “Thank you” to the other female volunteers who did not have shades of brown on their skin and could not understand their language like I did.

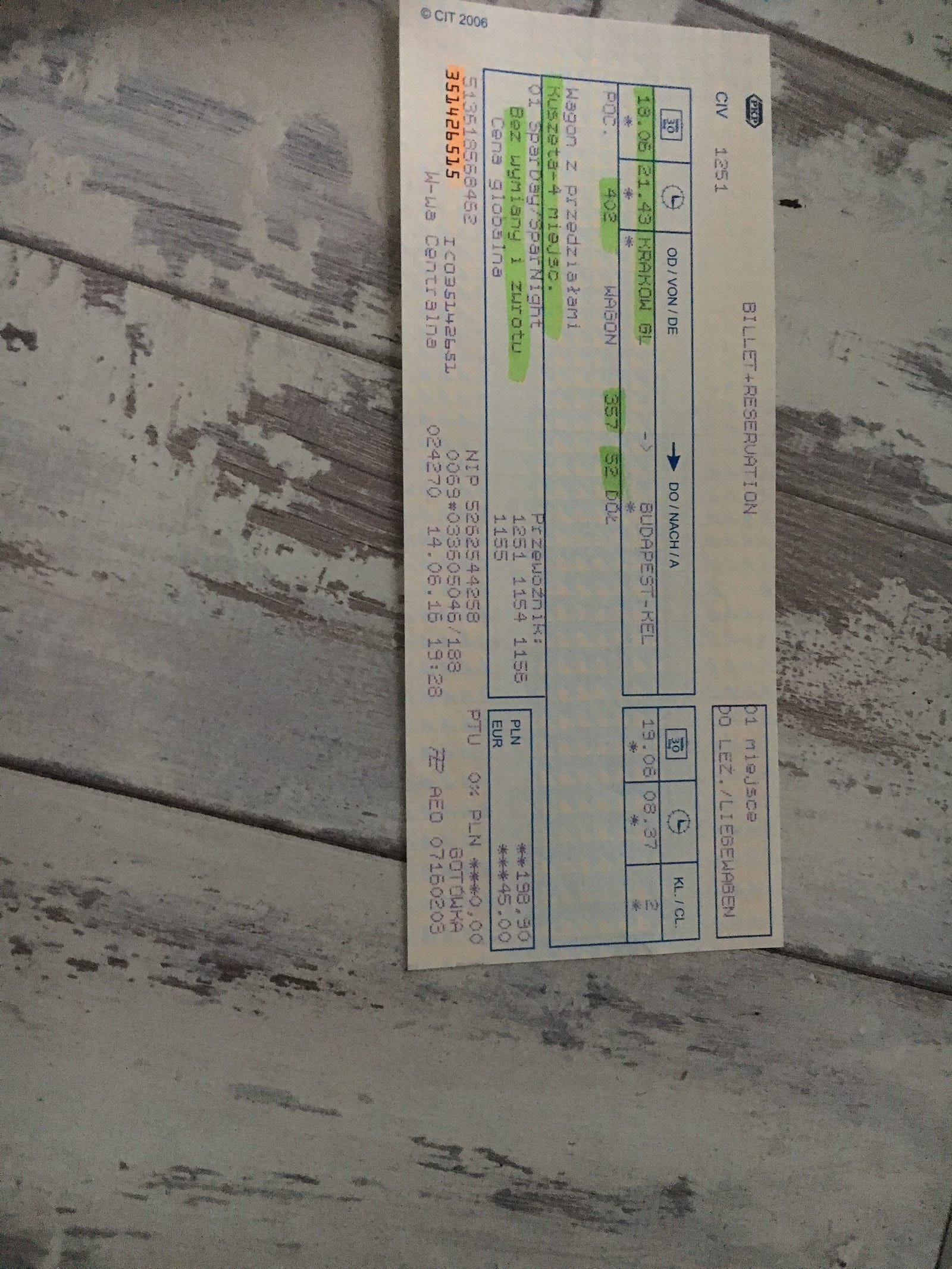

Degraded being refused train tickets because I did not speak the national language, at least this is what was said to me in English at the international desks at the Kraków Główny and Budapest—Nyugati pályaudvar (rail stations). Being pulled aside for body checks amongst groups of tourists at the historical sites of Holocaust remembrance I visited for work and tourism.

Train from Kraków Główny to Budapest-Nyugati pályaudvar

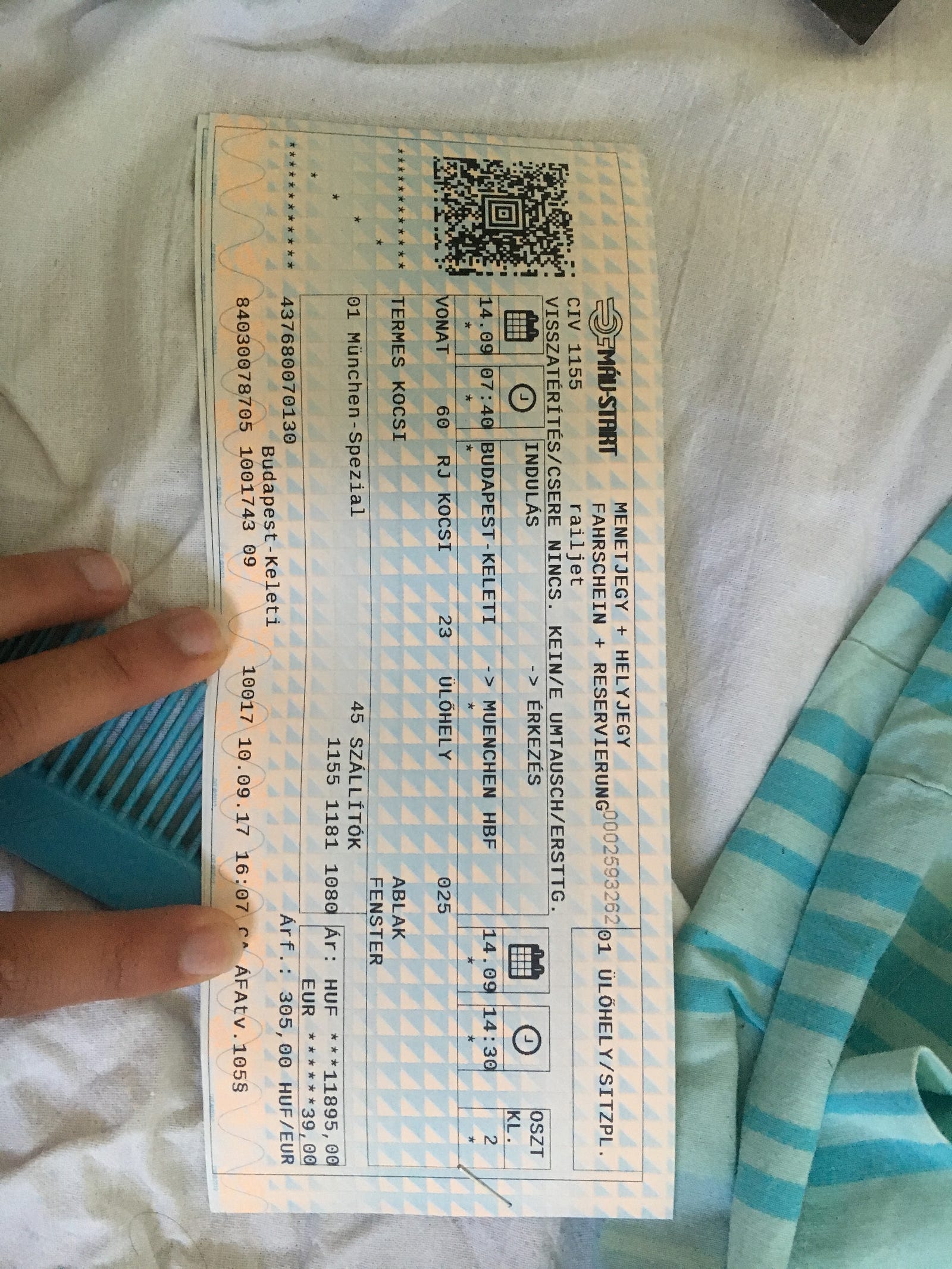

Fear watching women who pulled their children away from me and hearing the word “Cigányok” (Roma and Sinti, “Gypsy”) around me during rides on the Budapest underground to my office. Running from two men who cornered me on the city rail. And during my visit this past summer, the same fears arose being told I could not buy a train ticket to Munich at the Budapest-Nyugati pályaudvar (rail station) this past summer because I did not speak the language.

Fear watching women who pulled their children away from me and hearing the word “Cigányok” (Roma and Sinti, “Gypsy”) around me during rides on the Budapest underground to my office. Running from two men who cornered me on the city rail. And during my visit this past summer, the same fears arose being told I could not buy a train ticket to Munich at the Budapest-Nyugati pályaudvar (rail station) this past summer because I did not speak the language.

Budapest-Nyugati pályaudvar to Munich Hauptbanhof, 2017.

After being “Other” to people I worked with, lived with, and helped and facing their fears of me during the Summer of 2016, I came home freed of my own prejudices but deeply confused about my belonging and purpose.

I came home to an America mocking the hatred it truthfully felt, watching my classmates wear “Build a Wall” t-shirts and neighboring immigrants vote for anti-immigration policies.

I confronted my fear of self in this distorted environment of liberty and exclusion by speaking against the childhood and teenage silences of trauma and exclusion.

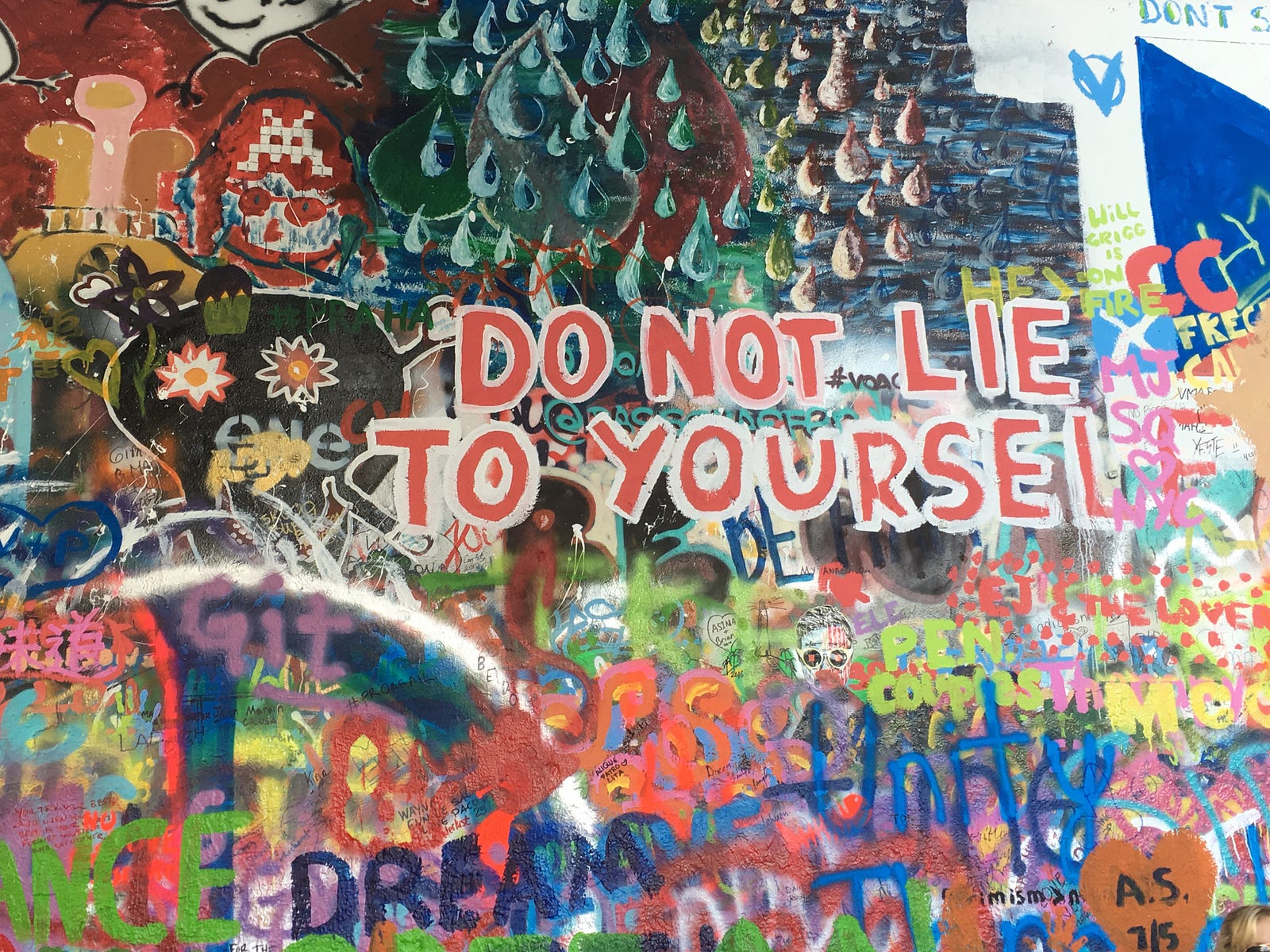

John Lennon Wall, Prague, Czech Republic.

I chose to advocate for mental health at my campus in Los Angeles, sharing my experiences of self-destruction and isolation in the form of a music video, which thousands viewed and spread across the country.

Age 17.

In confronting the walls I had built in my mind for self-preservation, I found the limitations I had created, starting with the denial and silencing of my pain as a witness and survivor.

My personal struggles with an eating disorder (anorexia nervosa) and depression from the ages of 13–19 had silenced my sense of self.

#MeToo became a silent acknowledgement of the fear and loss of integrity under re-traumatization I began facing under university and local healthcare systems intent profiting from my access and my rights to privacy.

Liberation of self began with the self-acceptance of my disability and the awareness of my power of choice as a human.

Self-acceptance of my humanity,

the grey choices of self and others

Liberation of self was only achieved by recognizing the humanity in another, especially those who do not share my perspectives and experiences.

Meeting one of 200 families from Syria resettled in Southern California confronted me with the reality of dehumanization happening at my doorsteps in silence.

Both parents take their only day off from work to learn English so that their girls and boys can have equal opportunities of education in American public schooling. They have independently learned to speak English at an A2 level in five months.

Some in media and politics say they are new social welfare recipients and are creating debt and creating instability for their children.

But who is actually creating the debt and instability in the violence of exclusion and silence of profit?

Me

I deny the very fabric and success of my country when I do not speak for myself.

My silence values money over my life.

Mental Health American National conference.

Today, I am a three-week old resident of Berlin, afraid and excited of what tomorrow will bring.

I first learned German language because of love.

I studied it for a year in Los Angeles inspired by the people I have spent three years listening, recording, and writing the life histories of their survival and displacement from the Holocaust and Armenian Genocide.

Interviewing a Holocaust survivor for the USC Shoah Foundation— The Institute for Visual History and Education where I have worked as a research assistant since August 2014.

I just experienced my first snowfall.

I enjoyed a sauna without clothes for the first time.

I am very grateful for my slate and the dust it has seen

I am just Mahima

I do not claim to represent the thoughts and experiences of anybody I work with, live with, and/or assist. I only promise to act and report with integrity, respect the consent and privacy especially of women and children in the most vulnerable conditions, and be welcoming of all perspectives and experiences.

I joined the GSBTB Open Arts Shelter because I am passionate about lifting people’s voices and want to grow as an individual as part of my new community here in Berlin by doing what I love most—learning. I thank with all of my heart these incredibly talented and beautiful children for teaching me how to be open-minded and for inspiring my music and writing here in my first weeks in Berlin.

I do not use the word “refugee” to describe or interact with people, rather the truth of individuals and families who are forcibly displaced under conditions of mass violence and dehumanization and in the forced process of resettlement in the greater Berlin area.

I will not document our work as cultural integration as many of us are not native to Germany and also have immigrant status here for our jobs and higher education. I believe that all humans are equal and should not be treated or addressed by their unchosen circumstances.

A child is a human before he or she is a refugee and/or asylum seeker. The word “refugee” is constantly being misused by media, governments, schools, and businesses internationally for profit. A child’s internalization of this label in the cultural integration programs they are growing up in, especially here where fluency in German is a requirement for work and education, are sources of both inclusion and exclusion.

I will also do my best not to project my own values and perspectives of equality onto the coverage of those raised by religions, social structures, and cultures where equality is not a norm.

It was at the Hungarian-Serbian border that I confronted a division I had only heard of growing up in Southern California and experienced in college as Pakistani and Indian Americans created separate culture shows and student groups. Many of the Pakistani individuals I met in camps wanted me to translate their Urdu and Hindi to get supplies from the Hungarian and Serbian volunteers, while the individuals from Afghanistan and Syria invited me for cups of chai and songs in Hindi in tents and made efforts to speak to me in Hindi and English.

I do not know how the children at the shelter feel about seeing a woman with a similar skin color raised on soil similar to the country they have just been forced to resettle in.

I wonder if inequality is natural, if at all children notice it. Is there an age of awareness?

As a father explained when I first joined, I’m closest to understanding them. But is that really so, when I am perceived as different in their standards because I do not speak their language nor do I know what it is like to grow up knowing that I am unequal because of my physical and sexual characteristics, as my mother and many women have known in India?

I am not alone in feeling this “Otherness.”

Exclusion is a reality many experience as an individual with a heritage that crosses man-made boundaries. While I do not let my heritage, choices and experiences create prejudices in my mind, I wish to acknowledge these differences of my experiences of working with people who are labeled as refugees and asylum-seekers in the EU.

I unconditionally believe in the equal value of all lives. I wish to be as open-minded as these children about present and the future. I thank their families for welcoming and trusting us in this difficult period.

4 year old Master Chef crafting cookies from scratch.

As my team leader Hania says, “We do things when we do not do things. The role of respectful dialogues, loving attitudes towards children of all genders and nationalities is maybe the best teacher of equality.”

With everlasting gratitude and hope,

Mahima

This post was originally published on Medium, where you can find more posts by Mahima. All photography by Mahima.